IN 2004, PROFESSOR EDWARD “TED” ADELSON WAS FOCUSED ON A SUCCESSFUL CAREER STUDYING HUMAN AND ARTIFICIAL VISION.

Then he had children.

“I thought I’d be fascinated watching them discover the world through sight,” says Adelson, the John J. and Dorothy Wilson Professor of Vision Science in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT. “But what I actually found most fascinating was how they explored the world through touch.”

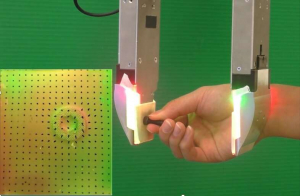

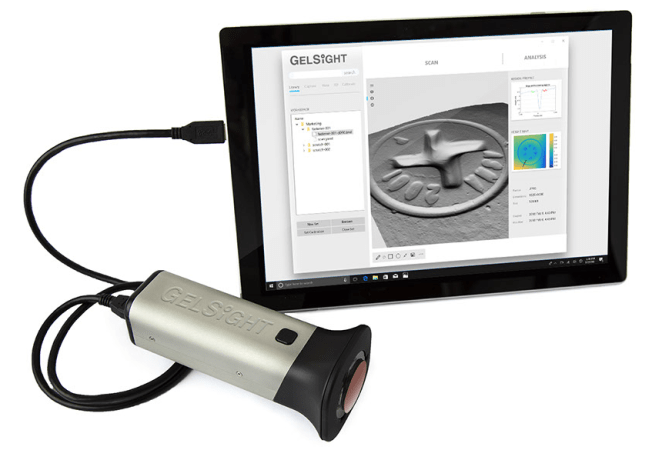

That fascination led Adelson to invent a touch-based technology: a sort of artificial finger consisting of a gel-based skin covering an internal camera. The device could chart surface topographies through physical contact—creating something like sight through touch. That technology is now the lifeblood of GelSight, the startup that Adelson founded in 2011 along with two MIT colleagues.

Originally “a solution in search of a problem,” as Adelson describes it, GelSight now produces bench-based and handheld sensors deployed for quality control in industries such as aerospace and consumer electronics. The company is also pursuing other commercial applications. Based not far from MIT in Waltham, Massachusetts, GelSight is closing its second round of financing and appears poised for profitability.

On the surface, GelSight’s story reads like another MIT cradle-to-corporation fairy tale. But the team’s odyssey from concept to company was filled with complex passages the founders were ill-prepared to navigate.

“We were academics,” Adelson recalls. “We had this technology and thought it would be easy to transform it into a profitable enterprise. We learned very quickly that the technical invention is the easiest part for people like us. Developing a product and building a company is way harder. That requires the effort and expertise of many smart people who must work a very long time. Fortunately, we had great connections available to us through the MIT community. The resources we were able to tap into at MIT were essential in creating and sustaining GelSight.”

Cofounders meet on campus

Adelson’s first collaborator in developing the underlying technology was Kimo Johnson, who joined his laboratory as a postdoc in 2008. “Ted had invented this material that could make very precise measurements in 3-D,” says Johnson, CEO and cofounder of GelSight. “We published several papers on the technology as academics tend to do. But we also made videos and posted them on YouTube. The response was amazing. My inbox was flooded with emails asking about potential applications. That was when we realized we should form a company.”

“The technical invention is the easiest part for people like us. Developing a product and building a company is way harder,” Adelson says.

As a first step, Johnson collaborated with students in a course called iTeams at the MIT Sloan School of Management to draft a hypothetical business plan built around GelSight technology. The plan proposed a potential application in the inspection of helicopter blades. That exercise helped him understand how valuable a handheld device that employed GelSight technology could be to professionals who inspect and repair critical surfaces. “This was another piece of information that encouraged us to move forward,” says Johnson.

Adelson and Johnson met GelSight’s third cofounder in 2010 at an on-campus seminar on imaging and computer vision. János Rohály, a former MIT research scientist, had founded Brontes Technologies in 2004. That startup, which applied computer vision in dentistry, was acquired in 2006 by 3M. It was the incarnation of every MIT startup’s dream.

“After my talk, Ted and Kimo introduced themselves and told me about GelSight,” recalls Rohály, who is now CTO of GelSight. “I was captivated by their technology and invited them to make a presentation to my colleagues at Brontes. A little later I realized I was losing sleep fantasizing about their technology. In 2011, when they formed the company, they reached out to me. I had the entrepreneurial experience and the knowledge of the MIT network that could help them. And I joined the team.”

Tapping MIT’s broad network

With Rohály on board, the GelSight team turned to MIT’s teeming startup network for help plotting its next crucial steps. “MIT sits in the middle of the Boston-area startup ecosystem,” says Adelson. “This ecosystem is populated with technologists, investors, business people, lawyers, and other professionals. Together they form a vibrant group of people who are constantly networking, sharing ideas, and encouraging each other. That energy and activity is critical to launch a startup company. It was for us.”

The MIT ecosystem delivered in a big way for GelSight. The company’s founding trio received consistent support and encouragement from the MIT Venture Mentoring Service (VMS), which provided business advice, financial guidance, and introductions to potential manufacturing partners, customers, and investors. (VMS will be celebrating its 20th anniversary in 2020.)

“Neither Ted nor I had the slightest business experience,” says Johnson. “At the Venture Mentoring Service, we could rely on seasoned entrepreneurs who were ready to share their experience and expertise with us. There are so many challenges a fledgling company faces. Negotiating contracts, for example. It takes an experienced entrepreneur to know where to make concessions and where to push back. We got that and much more from the Venture Mentoring Service. In the early days, they almost served as a board of directors for us.”

GelSight got another big boost when their technology was featured in a 2011 MIT News article. “That article generated an enormous amount of interest,” says Johnson. “There are so many subscribers across so many industries. And MIT News gets copied on so many technical news sites. In fact, it was that article that connected us to a person in business development, who in turn connected us to our biggest consumer electronics customer.”

GelSight’s founders also made critical connections through the MIT Deshpande Center for Technological Innovation and the MIT Technology Licensing Office. The MIT Industrial Liaison Program put the young company in touch with a series of potential customers, including Boeing. “In our first years, we essentially bootstrapped the company, selling benchtop systems to customers in industries including cosmetics, abrasives, and aerospace,” says Johnson. “These were mostly connections we’d made through MIT. And they were enough to keep us going and slowly growing.”

Unlike many startups, which seek rapid growth and an early sale, GelSight has plotted a more gradual growth curve. In 2014, thanks to a connection obtained through the MIT network, the company received an inquiry from a China-based manufacturer of smartphones. That company had a slew of complex measurement problems they thought they might resolve with GelSight’s capacity to measure surface topography. That sale—GelSight’s first large-volume order—changed both the company’s manufacturing practices and its focus.

“Up until that point, we’d been selling single systems to R&D laboratories,” says Johnson. “This sale showed us that our real value would be in quality control. We shifted toward process development and systems for mass production and inspection.” Buoyed by the China sale, GelSight held its first round of financing in 2015. Capital infusions came from Omega Funds—a Boston-based venture capital firm that specializes in biotechnology and medical device companies—and Ping Fu, a technology innovator and investor Rohály knew from his days at Brontes. Both Fu and Omega Funds managing director Richard Lim sit on GelSight’s board of directors.

Rohály credits MIT for much of the success in GelSight’s first round of financing. “MIT gives you a tremendous boost when you approach people,” says Rohály. “Just the name alone. This is true not only in technology circles, but also in business circles. Especially with investors. If you are from MIT or have technology invented at MIT, people are interested in seeing that technology.”

He also credits MIT and its ecosystem for sustaining the GelSight enterprise through all phases of its development. “There is a can-do attitude among MIT people that I have rarely seen elsewhere,” he says. “They can attend to any problem at any level and have the confidence in their ability to solve it. Too many times, in other venues, I’ve seen people stumble before problems because they don’t trust their ability to solve them. That doesn’t exist at MIT. When there’s a problem, [MIT people] say great, let’s start working on it.”

“MIT gives you a tremendous boost… especially with investors. If you are from MIT or have technology invented at MIT, people are interested in seeing that technology,” Rohály says.

In the past few years, GelSight has hit several important milestones. In 2017, the company successfully deployed its technologies at mass production and inspection facilities. The following year, GelSight was selected to provide surface inspection technology for the manufacturing operations of a top aerospace company.

This too has helped GelSight gain credibility with investors. “Until recently, investors would ask us whether people would actually buy our products,” says Johnson. “Now, when we have major companies selecting our technology to inspect their flagship products, that’s validation.”

In 2019, the cofounders say GelSight plans to step off the brakes and hit the gas. Over the past few years, the company has spent significant time and resources resolving scientific questions about the technology to ensure it can be produced on a broader scale. Now GelSight is working to close its second round of financing. This new capital will enable the company to ramp up manufacturing and accelerate its business plan.

“We’ve been extremely attentive to managing cash flow and operations,” says Rohály. “And we’ve found a nice sweet spot in aerospace and electronics. We’re also continuing to push for customers in new spaces. The amazing thing is that 90 percent of our current customers come from inbound interest, from customers reaching out to us and asking us to solve their problems.”

The GelSight team still seeks advice from partners in MIT’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. But now the company’s leaders also offer insight and advice to other MIT inventors seeking to bring laboratory creations to market. “We’re very much a part of the broad MIT network,” says Johnson. “We’ve learned firsthand how much can be gained by experienced professionals sharing their knowledge within a larger community. Now we’re in a position to give back to the community that has helped us so much.”

Original article published in MIT’s Spectrum Magazine:https://spectrum.mit.edu/summer-2019/a-helping-hand/